The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

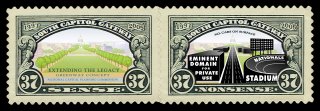

The article that I got the above illustration at http://www.alternet.org/rights/46384/ suggests that the Administration of George Walker Bush is most concerned about securing its effects from search by the U.S. Congress:

The Bush administration has been historic in its refusal to share information with Congress or the public. It has strong motivations to continue to conceal such information, such as avoiding humiliation, further public exposure, and probable criminal liability. It has sent strong signals it will indeed refuse to provide such information. As Time magazine wrote just before the election:

When it comes to deploying its Executive power, which is dear to Bush's understanding of the presidency, the President's team has been planning for what one strategist described as 'a cataclysmic fight to the death' over the balance between Congress and White House if confronted with congressional subpoenas it deems inappropriate. The strategist says the Bush team is 'going to assert that power, and they're going to fight it all the way to the Supreme Court on every issue, every time, no compromise, no discussion, no negotiation.

As a result, the

Indeed, that crisis has already begun. For example, just after the elections the Justice Department, in response to an ACLU suit, disclosed in court the existence of directives from the President and the CIA General Counsel that may have authorized torture and other illegal interrogation techniques. Sen. Patrick Leahy, incoming chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, immediately wrote Attorney General Alberto Gonzales requesting the documents and related records. On January 2, Leahy released a letter from the Justice Department refusing to provide the documents on grounds of national security and executive privilege. Leahy decried the refusal and added, "I have advised the Attorney General that I plan to pursue this matter further at the Committee's first oversight hearing of the Department of Justice."

This is just the first of what are likely to be myriad such conflicts. Both sides are likely to maneuver to determine the issues over which the climactic struggles will arise. The Administration will probably maneuver for issues on which it can make a strong national security case. Congress will probably seek to steer confrontation to issues like war profiteering on which the Administration will appear to be withholding information for self-serving reasons, e.g. avoiding embarrassment or criminal culpability.

Constitutionalists, progressives, and the public should support the congressional assertion of the right to know, whatever subject emerges as the decisive bone of contention. However, they should ensure that this does not become a means for either side to take other important but more controversial issues (such as the origins of the war and the commission of war crimes) off the table.

The Administration has been preparing for this situation for a long time; news reports indicate that even prior to the elections it hired lawyers specifically to plan for such a contingency. It is likely to use a variety of delaying tactics, diversions, and pseudo-compliances to bring the issue to a head at a time most advantageous to it. It is also likely to engage in counter-attacks, such as the recent attempt by its prosecutors to use a grand jury subpoena to force the ACLU to turn over all copies of a classified document. (The revocation of its demand also shows the effectiveness of firm resistance to Administration intimidation.)

Notwithstanding Administration delays and diversions, Congressional access to Administration documents is likely to become a serious power struggle quite rapidly after the opening of the new Congress. A plausible scenario looks something like this:

· A congressional committee will request information.

· The Administration will stonewall.

· The committee will issue a subpoena.

· Amidst a sea of justifications and vilifications, the

Administration will fail or refuse to produce documents.

· The committee will pass a contempt citation.

· The Senate or House will pass a contempt citation.

· The contempt citation will be referred to the Justice Department.

· The Justice Department will fail or refuse to bring contempt charges.

At that point Congress will have several options:

It can make angry noises while in actuality accepting Administration intransigence.

It can pass legislation establishing a special prosecutor.

It can appeal to the courts by suing the Administration.

It can establish a select committee or otherwise threaten impeachment against whatever officials it decides to hold accountable, from the President and Vice-President through cabinet members and other top officials.

What choice Congress makes will depend largely on public perception of and response to the situation. For example, in the Watergate scandal, public outrage at the "Saturday Night Massacre" tipped the balance toward congressional impeachment hearings. On the other hand, public disapproval of the attempt to impeach President Clinton actually contributed to a Democratic victory at the next elections.

Constitutionalists and progressives need to start planning proactively to prepare the public to respond appropriately and effectively to this impending confrontation.

First, that requires an on-going interpretation to people of what is happening and what it means.

Second, it involves defining venues for action in which large numbers of people can participate. Rep. John Conyers' mobilization of popular support for demanding information about the

Third, it requires creating some kind of infrastructure or rapid-response network with the capacity to support such a mobilization.

Fourth, it calls for a broad coalition that reaches far beyond progressives to include conservatives committed to the rule of law and a broad public concerned about the abuse of presidential power and the preservation of democracy. Such a coalition already exists in nascent form, for example in the Constitution Project, which has brought together such improbably allies as Al Gore and Bob Barr to articulate concern about Bush administration abuse of presidential power.

The power and willingness of Congress to affect Bush's

A defeat of the Bush administration on the right of Congress and the public to know what the government is doing can be the starting point of a broader effort to establish institutional and cultural vehicles for controlling executive power -- in short, for a transition to democracy.

Tagged as: constitution, crisis, documents, congress, white house, democrats

Jeremy Brecher is a historian and co-editor with Brendan Smith and Jill Cutler, "In the Name of Democracy: American War Crimes in

With all of what been written about the Administration of George Bush’s expansion of

His web site clearly indicates his pride in his accomplishment of throwing that first ball at the Washington Nationals 1st season in 2005 at R.F.K. Stadium.

Of course with this administration's secrecy, as written into the so-called "PATRIOT" act, how can his role, and that of his successors (or bosses) in such affairs, ever be known?

Of course with this administration's secrecy, as written into the so-called "PATRIOT" act, how can his role, and that of his successors (or bosses) in such affairs, ever be known?

No comments:

Post a Comment